Clinic Resource Manual

This resource manual has been developed by the CHFN to assist its members in the operation of a heart failure (HF) outpatient clinic. It provides an overview of a management structure for the clinic, identifies the clinic team, and describes the roles and responsibilities of each team member. The manual will be updated periodically by the education subcommittee.

This resource manual has been developed by the CHFN to assist its members in the operation of a heart failure (HF) outpatient clinic. It provides an overview of a management structure for the clinic, identifies the clinic team, and describes the roles and responsibilities of each team member. The manual will be updated periodically by the education subcommittee.

The current edition (Second Edition, August 2010) of the resource manual is divided into seven (7) parts. These parts correspond to the seven (7) sections of the resource manual listed below:

Preface

Heart failure (HF) has been a growing clinical problem in Canada and throughout the world resulting in reduced quality of life, recurrent hospitalizations and premature death.

Mission Statement

The mission of the Canadian Heart Failure Network (CHFN) is to provide appropriate, comprehensive, high-quality care to limit disability and improve the quality of life of patients with HF through exemplary outpatient management in outpatient HF clinics. Each clinic will be a centre of excellence for the clinical management of HF and will also serve as a resource centre dedicated to improve the quality and quantity of life for HF patients and their families.

About this Manual

This resource manual has been developed to assist health care professionals in the successful operation of a HF outpatient clinic. It provides an overview of a management structure for the clinic, identifies the clinic team, and describes the roles and responsibilities of each team member. A multidisciplinary approach is recommended where Physicians, Nurses, Dieticians, Pharmacists and other health care professionals provide collaborative advice and direction.

Because patient compliance is a key factor in the management of HF, an extensive patient education program is also included in this manual.

Medical management, care protocols and patient monitoring are key elements of the HF clinic and are included as guidelines to assist in the optimization of HF care across Canada.

Data collection using a flexible data-gathering tool is used to guide current and future practice, measure outcomes, determine quality of life (QOL) issues and track patient satisfaction. Periodic analyses of data collected allows practitioners to review and change practice patterns to enhance patient care and QOL. Ongoing data collection will also allow practitioners to demonstrate the cost-benefits derived from treating HF in the clinic setting.

This resource manual will be updated periodically as warranted by new research findings, changes in clinical practice guidelines, and continuing clinical experience.

Disclosure

This website was developed by the Canadian Heart Failure Network (CHFN) as an aid for health care professionals, heart failure patients, and lay persons to better understand heart failure and how it may be prevented and treated. The information and opinions provided are not a substitute for normal medical care provided by Physicians or other health care professionals, and are for general interest only. The advice and information do not constitute recommendation for changes in treatment for any particular individual, and the information may not apply to all patients or clinical situations. Mention of specific products, processes or services does not constitute or imply a recommendation or endorsement by the CHFN.

The CHFN assumes no liability arising from any error or omission in the information available on the website and recommends that you confirm with your Physician if a change in your management is required. Links to other websites are for your information and convenience only and CHFN accepts no responsibility or liability for the content or any advice in those external websites. When you link to an external website, you have left the CHFN website and the CHFN is not responsible for the privacy policies or content located within these external sites.

Sponsorship

This program is an independent national network with initial support from SmithKline Beecham Pharma and Hoffmann-La Roche and ongoing support from our corporate partners.

The impetus for the program came from Cardiology Physicians and Nurses from across Canada who envisioned the need for a common and comprehensive approach to the current management of patients with HF.

Comments/Suggestions

We welcome any comments and suggestions you may have regarding this important educational program. Kindly send them to:

Malcolm Arnold, MD, FRCPC, FACC

Chair, Working Group

Canadian Heart Failure Network (CHFN)

University Hospital - London Health Sciences Centre

C6-124D

339 Windermere Road

London, Ontario

N6A 5A5

www.chfn.ca

T: 519-663-3496

F: 519-663-3497

Rationale for HF Clinics

The Problem: Heart Failure

Heart failure (HF) is a major health problem in Canada and throughout the world. Presently, HF affects 5 million to 7 million North Americans and another 20 million individuals in Third World countries.1

In Canada, HF affects more than 1% of the population and is responsible for 9% of all deaths. HF is the most common cause of hospitalization of people over 65 years of age.2

The incidence and prevalence of HF will continue to rise as the population ages. As shown in Figure 1.1, it is estimated that HF prevalence will nearly double due to the aging population by the year 2030.3 In some regions of Canada, the rate of HF is increasing by as much as 4% annually.

Despite medical management, recent data suggest that the HF mortality rate may be as high as 40% to 50% two years following treatment.4 In addition, the continual cycles of acute crises associated with HF result in high hospital readmission rates and increased health care costs.

This steady increase in the number of deaths, hospitalizations, and medical costs associated with HF continues to occur at a time when morbidity and mortality rates from other common cardiovascular diseases (such as myocardial infarction) are on the decline.

There is an urgent need for aggressive measures to reduce the mortality and morbidity associated with HF, reduce hospital admissions and readmissions, and improve patient management.

|

One Solution: HF Clinics

In recent years, a number of HF clinics have been established in Canada and the United States in an effort to improve the quality of life of patients with HF and reduce the economic burden associated with the inpatient management of this patient population.

Preliminary findings from the Cardiology Preeminence Roundtable publication suggest that progress in the management of patients with HF depends on avoiding hospitalization in the first place.3

Figure 1.2 shows several approaches that are being successfully used to manage HF patients in the outpatient setting. 3

“As much as 50% of inpatient care for HF ideally should have occurred elsewhere or been avoided altogether.”

Cardiology Preeminence Roundtable3

|

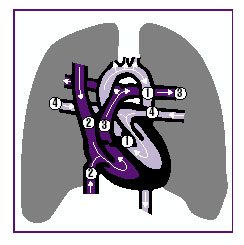

As shown in Figure 1.3, heart failure

clinics have the potential to reduce length of stay

and hospital admissions.3

“Outpatient intervention not only reduces HF admissions, but when hospitalization is unavoidable, it reduces the average length of stay.”

Cardiology Preeminence Roundtable3

|

Heart Failure

Heart failure (HF) is a state in which the heart is unable to pump blood at a rate to meet the requirements of metabolizing tissues or can only do so from an elevated filling pressure. Many forms of heart disease may lead to heart failure. Other diseases and treatments can precipitate exacerbations of HF.

Etiology of Heart Failure

- Ischemia/myocardial infarction 65%

- Non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy 20%

- Other 15%

Ischemia and/or myocardial infarction contribute to the development of heart failure in up to 65% of cases.5 Myocardial infarction can lead to ventricular remodelling with compensatory dilation and hypertrophy and subsequent systolic and diastolic dysfunction progressing to the clinical syndrome called HF. In patients with ischemia, the major cause of heart failure is systolic dysfunction with some degree of diastolic dysfunction.

In a subgroup of patients, the cause of heart failure is diastolic dysfunction. These individuals have signs and symptoms of heart failure but a normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Appropriate management of these patients is to address the underlying etiology. Unfortunately, there are few clinical trials to direct decisions about the best choice of drug therapy.

Some patients have signs of HF such as cardiomegaly on chest x-ray or left ventricular dysfunction, but no symptoms.

Goals of Heart Failure Treatment

The clinical goals of heart failure treatment are to:

- Improve heart function

- Reduce symptoms

- Prevent hospital readmissions

- Improve survival

- Improve quality of life

Disease Progression in Heart Failure

Most patients with heart failure have only mild symptoms and often respond well to medical therapy. Unfortunately, because of the progressive nature of HF, these patients remain at risk for worsening disease despite the optimal use of current firstline medications. This is because myocardial damage triggers a series of compensatory mechanisms that progressively compromise cardiac function.

In the early stages of myocardial damage, activation of neurohormonal systems, including the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAA) and sympathetic nervous systems, provides initial support for the failing heart. However, the continued neurohormonal activation becomes deleterious with excessive vasoconstriction, volume expansion, and ventricular remodelling leading to continued deterioration in cardiac function.

Ventricular remodelling can be favourably altered by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, agents that have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with HF and asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction.6

Recent clinical findings suggest that beta-blockers can reduce symptoms, improve left ventricular function, and inhibit disease progression in patients with mild to moderate HF on standard therapy consisting of an ACE inhibitor and diuretics, with or without digoxin.7-10

Emerging data on the beneficial effects on outcome in heart failure patients with beta1-selective blockers further support the importance of this therapy.11,12 However, in a meta-analysis of the clinical effects of beta-adrenergic blockade in heart failure, Lechat and colleagues reported that the reduction in mortality risk was greater for nonselective beta-blockers than for beta1–selective agents.10

Diuretics are very successful in reducing symptoms of HF and they probably reduce readmissions for heart failure. However, their influence on survival has not been adequately tested. Digoxin can improve symptoms and will reduce hospital readmissions for heart failure, but has a neutral effect on survival. Some positive inotropic agents will reduce symptoms and hospital readmissions for heart failure, but may worsen the underlying disease process.

References

- Ackman ML, Harjee KS, Mansell G, et al. Cause-specific noncardiac mortality in patients with chronic heart failure — a contemporary Canadian audit. Can J Cardiol 1996;12:809-813.

- Brophy JM. Epidemiology of chronic heart failure. Canadian data from 1970-1989. Can J Cardiol 1992;8:495-498.

- Cardiology Preeminence Roundtable. Beyond Four Walls: Cost-Effective Management of Chronic Congestive Heart Failure. Washington, D.C.: Advisory Board Company, 1994.

- Johnstone DE, Abdulla A, Arnold JMO, Bernstein V, et al. Diagnosis and management of heart failure. Can J Cardiol 1994;10:613-631.

- Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Report on the 1993 Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Heart Failure. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 1996.

- The SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. N Engl J Med 1992;327:685-691.

- Doughty RN, Whalley GA, Gamble G, MacMahon S, Sharpe N. Left ventricular remodeling with carvedilol in patients with chronic heart disease due to ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;29:1060-1066.

- Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, et al, for the U.S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1349-1355.

- Heidenreich PA, Lee TT, Massie BM. Effect of beta-blockade on mortality in patients with heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:27-34

- Lechat P, Packer M, Chalon S, Cucherat M, Arab T, Boissel J-P. Clinical effects of ß-adrenergic blockade in chronic heart failure. Circulation 1998;98:1184-1191.

- CIBIS Investigators and Committees. A randomized trial of ß-blockade in heart failure: the Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study (CIBIS). Circulation 1994;90:1765-1773.

- The International Steering Committee on Behalf of the MERIT-HF Study Group. Metoprolol CR/XL. Randomized Intervention Trial in Heart Failure (MERIT-HF): rationale, design, and organization. Am J Cardiol 1997;80(Suppl 9B):54J-58J.

*Draft changes pending adoption by CHFN

The HF Clinic

Establishing a Heart Failure Clinic

Informing the Community

HF clinics offer an effective alternative to the current cycle of acute care management. They offer complete patient evaluations, education, regular monitoring, and immediate response to patients’ clinical needs.

In addition, HF clinics offer long-term benefits to patients, families, and the communities they serve. It is expected that each local HF clinic will be a centre of excellence for the clinical management of HF and a resource centre dedicated to improving the lifestyle of HF patients and their families.

Objectives of Heart Failure Clinics

- Improve patient care

- Provide medical care in a timely fashion

- Optimize the use of proven medical therapies

- Educate HF patients about all aspects of their condition

- Improve cardiac function

- Improve quality of life

- Empower patients with the knowledge/capacity to manage heart failure

- Reduce hospital admissions and readmissions

- Reduce morbidity and mortality

- Disseminate the latest information on HF

- Serve the community

- Quality of care assessment

Facility Profile

Clinic Accommodations

- Examination rooms, waiting area, meeting room, offices, exercise room, telemonitoring, telephone follow-up

Equipment

- Office equipment, computers, tables, chairs, blood pressure machines, scales, echocardiograph, treadmill, bikes

Operating Costs

- Part-time cardiologist(s)

- Full-time clinic staff: nurse manager/coordinator, clerical staff

- Telephone costs, Internet access

- Clinic supplies, office supplies

Access/Referral to

- Electrophysiology, CRT, ICD

- Cardiac Surgery

- Transplantation team

HF Clinic Team

The clinics will be Physician-directed and Nurse-managed. The on-staff Cardiologist will perform all initial assessments and examinations, and then develop a treatment plan that will be implemented and managed by the Clinic Nurses.

The Nurse Manager/Clinic Nurse is experienced in cardiology and may have some experience in the outpatient setting. In many settings, Nurses with advanced training are responsible for patient management and the implementation of delegated medical tasks.

Along with the Nurse(s) and the Cardiologist, the clerical staff are considered primary members of the clinic team. They will perform daily administrative duties and assist in data collection and data entry.

Secondary team members who may be affiliated with the clinic on either a part-time, full-time, or referral-only basis include: Pharmacists, Dietitians, Psychologists, Social Workers, and Exercise Physiologists or Physical Therapists as well as EEP Cardiologists and Cardiac Surgeons.

Pharmacists are important members of the clinic’s multidisciplinary team. They provide both patients and staff with information concerning drug interactions, pharmacokinetics of drug action, side-effects of medications, and dosing adjustments required for comorbid conditions. Counselling by a Clinical Pharmacist has been shown to increase patient compliance with medication regimens, resulting in improvements in peripheral edema and physical capacity.1,6

Referrals to a Registered Dietitian are particularly important for HF patients suffering from comorbid conditions such as diabetes or renal failure. The Dietitian will educate patients about the need for sodium and fluid restriction, assess protein and caloric requirements, and incorporate dietary changes needed to manage comorbid conditions.

Depression, anger, and frustration related to decreased quality of life are common among HF patients, particularly those patients with poor psychosocial adjustment to their situation.2 Therefore, referral to a Clinical Psychologist may be necessary. Counselling by a Psychologist can help patients and their family members adjust emotionally to the difficult lifestyle changes required for HF management.

The primary role of the social worker is to develop an individualized living plan for the HF patient. This plan may include making arrangements for food/meals, transportation, home assistance, and providing access to financial assistance. The Social Worker can also assist patients and their family members in finding support groups that provide open discussions of common issues such as work, sexuality, exercise and leisure activities, and the adjustments that must be made to each.

Although HF patients have traditionally been encouraged to modify physical activity, exercise rehabilitation programs have been used successfully to improve the functional capacity of HF patients.3,4 Therefore, an Exercise Physiologist or Physical Therapist may be affiliated with the clinic to establish an appropriate exercise regimen for the HF patient, provide instruction on exercise limitations, and monitor the exercise program.

In addition to the secondary team members, heart failure clinics may be affiliated with Occupational Therapists, Home-care Providers, Palliative-care Physicians, patient-support groups, transplant teams, members of the clergy, and volunteers. Although not core members of the clinic team, these individuals are highly valued members of a successful clinic program. For example, Home-care Providers are particularly important for the management of older HF patients who may have difficulty performing daily activities such as bathing and sitting in a chair. Also, palliative-care counselling may be required for the emotional well-being of both patients and their family members. Many patients find psychological relief in the ability to talk openly about the mortality associated with heart failure, and preparation for death.5,6,7,8,9

Patient Selection

Heart failure clinics are outpatient facilities that offer a comprehensive approach to HF management. All patients with suspected and established heart failure (NYHA Classes I to IV) should be eligible for treatment at these clinics. Referrals to the HF clinic are accepted from any source: community Physicians, hospital-based Physicians, and other clinics. Nurse and patient-facilitated referrals for education may also be accepted.

| Clinic director | Responsibilities |

| Cardiologist | • Receives patient referrals • Performs initial evaluations • Establishes medical regimen • Sees patient regularly • Liaises with Nurse Manager before any major changes in medical intervention |

| Nurse Manager

Registered Nurse with cardiology experience |

• Implements treatment plan • Educates patient • Adjusts medications (using drug management protocols) • Schedules patient appointments • Makes regular follow-up calls |

As shown in Figure 2.1, patient education

is key to the success of a HF management

program. Education should involve all members of the multidisciplinary

clinic team and

should be ongoing.

Data Collection

Data collection can be used by heart failure clinics for the following purposes:

- To monitor patient care issues and outcomes

- To track public health data

- To document the need for the clinic

- To secure funding

- To answer research questions

References

- Uretsky BF, Pina I, Quigg RJ, Brill JV, et al. Beyond drug therapy: nonpharmacologic care of the patient with advanced heart failure. Am Heart J 1998;135(Suppl 2):S264-S284.

- Dracup K, Walden JA, Stevenson LW, Brecht M-L. Quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 1992;11:273-279.

- Coats AJS, Adamopoulos S, Radaelli A, et al. Controlled trial of physical training in chronic heart failure. Circulation 1992;85:2119-2131.

- Sullivan MJ, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR. Exercise training in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 1998;78:506-515.

- Hauptman PJ, Rich MW, Heidenreich PA et al. The Heart Failure Clinic: A consensus statement of the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Card Failure 2008; 14: 801-815.

- Gattis WA, Hasselblad V. Whellan DJ, O'Connor CM. Reduction in heart failure events by the addition of a clinical pharmacist to the heart failure management team: Results of the Pharmacist in Heart Failure Assessment Recommendation and Monitoring (PHARM) study. Arch. of Internal Medicine 1999;159(16): 1939-1945.

- Albert NM, Fonarow GC, Yancy CW et al. Influence of dedicated heart failure clinics on delivery of recommended therapies in outpatient cardiology practices: Findings from the Registry to improve the use of Evidence - Based heart Failure Therapies in the Outpatient Setting (Improve HF). Am Heart J 2010; 159:238-44.

- McAlister FA, Stewart S, Ferrura S, McMurray JJJV. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: A systematic review of randomized trials. J. Am Coll. Cardiol.2004; 44:810-819.

- Focused Update Incoporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation / American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2009;119:391-479.

*Images provided by Microsoft Clip Art

Medical Management

Running a Heart Failure Clinic

1. Scope

This document provides strategies for the improved diagnosis and management of adults (19 years and older) with heart failure (HF). It is intended for primary care practitioners, allied health professionals and patients with HF. It focuses on approaches needed to provide care to patients with this complex syndrome.

2. Diagnostic Code:

428

3. Clinical Highlights

HF is a complex syndrome associated with a high rate of hospitalization and short-term mortality, especially in elderly patients with comorbidities. Early diagnosis and treatment can prevent complications.

- Successful HF management begins with an accurate diagnosis. All patients should have an objective determination of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by echocardiogram, or radionuclide ventriculogram (RNV) if echocardiogram is unavailable

- Treat underlying vascular risk factors (see guidelines on Hypertension and Diabetes Care), comorbidities and other chronic diseases

- Patient and caregiver education should be tailored and repeated

- Encourage the patient to accept responsibility for their HF care through an individualized management plan with self-care objectives, including salt restriction, weight monitoring and medication adherence strategies

- Reinforce the importance of healthy lifestyle modifications, including healthy eating, regular exercise, weight management, social support and smoking cessation

- Treatment requires combination drug therapy

- All systolic HF patients should receive an ACE-I and a BB at target dose unless contraindicated. These therapies should be considered in all patients with HF with preserved systolic function (PSF)

- Additional therapy should be guided by clinical situation

- As polypharmacy remains a concern - match drugs to goals of treatment

- Care should be individualized based on symptoms, underlying cause, disease severity and goals of care

- Plan effective systems to ensure follow-up and patient education to improve outcomes

- Engage patients in open discussions on the end of life issues

4. Prevention of Heart Failure

- Assess all patients for known or potential risk factors for HF (hypertension, ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and tobacco use)

- Modifiable risk factors should be treated according to current guidelines

- Routine screening for asymptomatic LV dysfunction is currently not recommended

- For selected patients at high risk for HF due to multiple risk factors, the decision to screen (such as by echocardiography) should be individualized

- The prognosis of HF at the earliest appropriate time

5. Patients with Asymptomatic LV Dysfunction

- ACE-I should be used in all asymptomatic patients with LV dysfunction and

LVEF < 40% - BB should be considered in all patients with asymptomatic LV dysfunction

and LVEF < 40% (especially if there is a history of ischemic heart disease)

6. Diagnosis of Heart Failure

HF is under diagnosed in its early stages. Diagnostic accuracy improves when there is a high index of suspicion and a consistent approach to diagnosis.

7. Definition of Heart Failure

HF is a clinical syndrome defined by symptoms suggestive of impaired cardiac output and/or volume overload with concurrent cardiac dysfunction. While a normal LVEF is >60%, the threshold of 40% is used for the purposes of diagnostic classification. As such, HF can be classified into systolic heart failure, as defined by the presence of signs and symptoms of HF with an LVEF <40%, and heart failure with preserved systolic function (HF with PSF – previously called diastolic dysfunction) is defined by the presence of signs and symptoms of HF in the absence of systolic dysfunction (LVEF ≥ 40%). Prognosis for systolic HF is significantly worse than HF with PSF. Research evidence for treatment is best established for systolic HF but, in general, the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies are similar for both.

8. Evaluation of HF should include:

- A thorough history and physical exam focusing on:

- Current and past symptoms of HF (i.e. fatigue, shortness of breath, diminished exercise capacity and fluid retention/weight gain)

- Functional limitation by New York Heart Association (NYHA)

- Cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and other comorbid conditions

- Assessment of a patient’s endurance, cognition, and ability to perform activities of self-management and daily living

- Assessment of volume status (e.g. peripheral edema, rales, hepatomegaly, ascites, weight, jugular venous pressure, and postural hypotension)

- Initial investigations in all patients (where available):

- Complete blood count

- Serum electrolytes

- Creatinine (Cr), eGFR

- Urinalysis

- Microalbuminuria

- Fasting blood glucose

- Fasting lipid profile, AST

- Albumin

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- 12-lead electrocardiogram and chest radiograph

- All patients should have an objective determination of LVEF by transthoracic echocardiogram (preferred as it also provides information on cardiac dimensions, valvular function and may suggest the underlying etiology of HF) or RNV if echocardiogram is unavailable

- BNP has high diagnostic value for both types of HF and is recommended where available, when diagnosis is unclear. The use of BNP in non-acute heart failure and community outpatient practice remains to be clarified. (See Table 1)

- In cases where there is doubt, or an objective determination of LVEF is not immediately available, response to a therapeutic trial may increase the diagnostic accuracy (See Figure 1)

- When the etiology of HF is uncertain, consider referral for more specialized cardiac testing as clinically indicated

9. Non-Pharmacologic Management Strategies

HF care depends on the patient’s understanding of, and participation in, optimal care. Patients can be important partners in individualized goal setting, salt restriction, weight monitoring, and adherence.

9.1. Goals of Care

- Determine the goals of managing their HF with the patient, i.e. aggressiveness from a goal of an advanced cardiac technology and transplantation through to a goal of symptom control and palliation

- Identify an appropriate substitute decision maker (health proxy)

- Advance Directives / Representation Agreements regarding end-of-life care should be addressed at the earliest appropriate time

- Above decisions should be reviewed regularly and specifically when there is a change in the patient’s clinical status

9.2. Self-Monitoring

- Discuss the importance of self-management with the patient and their network of support

- Work with the patient on the specifics of the plan as outlined below (9.3-9.9)

9.3. Weight

- All patients should be encouraged to weigh themselves daily and recognize symptoms of worsening HF

- Initially: Report a weight gain of 2.5 kg/week or a worsening of symptoms

- Goal: Self-assessment and adjustment of fluid/sodium restriction and/or diuretic dosing in response to a weight gain of ≥1 kg (patient-based algorithm)

9.4. Salt Intake

- All HF patients should limit sodium intake, avoid processed foods and avoid adding salt

- Review salt intake when weight gain is experienced

9.5. Fluid Intake

All HF patients with hyponatremia, or severe fluid retention/congestion that is not easily controlled with diuretics, should limit fluid intake to 6-8 cups of liquid/day (1 cup = 8 ounces = 250 mL), including frozen items and fruit (1 serving = 1/2 cup of liquid).

9.6. Alcohol

Not more than one drink per day is recommended. This is equal to a glass of wine (5 oz./150 mL/12% alcohol), beer (12 oz./350 mL/5% alcohol), or one mixed drink (1 1/2 oz./50 mL/40% alcohol). In alcohol related heart failure, alcohol must be totally avoided.

9.7. Exercise Training

- All HF patients with stable symptoms and volume status should undertake regular, moderate intensity physical activity (aerobic and resistance exercises to maintain muscle mass)

- Aerobic physical activity: Start with 5-10 minute sessions every other day, working to a goal of 30-45 minutes per day 4-5 days per week

- Resistance exercises (do 10-15 repetitions at 50-60% of normal effort)

9.8. Immunization

All HF patients should be immunized for influenza (annually) and pneumococcal pneumonia (if not received in the last six years) to reduce the risk of respiratory infections.

9.9. Collaboration with complementary health care providers

- Involve Nurses, Pharmacists, Dieticians and Cardiac Exercise Therapists for individual or group visits when possible

- A Dietician can provide valuable education regarding the practical aspects of implementing a salt and water restriction, how to make healthy food choices and/or a group grocery store tour to help facilitate low-salt food and drink selections

- A Pharmacist may help patients remain on therapy when they are faced with side-effects and provide useful advice to help with medication compliance

- A Cardiac Exercise Therapist may be instrumental in helping HF patients develop and continue a structured exercise program

10. Pharmacotherapy for Heart Failure

- In general, research evidence for treatment is best established for systolic HF, although the underlying principles and pharmacotherapy also apply to HF with PSF. However, when treating HF with PSF, extra caution is required with ACE-I, vasodilators and diuretics to prevent symptomatic hypotension or pre-renal failure as LV filling pressures are volume dependent

- It is important to treat the following underlying cause where possible, especially in the case of HF with PSF:

- Hypertension (goal is blood pressure <140/90 mmHg)

- Ischemic heart disease

- Atrial fibrillation (goal ventricular rate between 60-80 at rest and <110 with exercise)

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (consider referral to specialist)

- All patients with systolic HF should be on an ACE-I and a BB unless contraindicated (these medications should be strongly considered in patients with HF with PSF)

- Historically, an ACE-I was started first and titrated to target dose before starting a BB but current evidence suggests that it does not matter which drug is started first as long as both are titrated to target dose

- See Appendices regarding medication initiation and titration - BB should not be initiated in patients with volume overload

- ARB can be substituted for BB or ACE-I if they are not tolerated

- ARB can be cautiously added to patients with persistent symptoms despite optimal ACE-I and BB dose

- In the elderly, initial doses should be low and titrated slowly

- Concerns may arise as these medications are titrated upwards

Blood Pressure:

- When the systolic BP is below 80 mmHg, limit increase in medication if the patient shows symptoms of low BP (consider measuring postural vitals in the elderly)

- Take blood pressure lowering medication with food

- Separate the dosing of blood pressure lowering medications by at least 2 hours (i.e. give the ACE-I at noon and BB in the morning and at bedtime)

- If hypotension occurs during medication titration consider:

- Adding a higher dose at bedtime first, then increase the morning dose (if BID dosing)

- Decrease or discontinue the diuretic and/or vasodilator

- Consider temporarily reducing the ACE-I dose during BB titration

- Decrease the BB dose by 50% and reinitiate titration once condition stabilizes

Renal Function:

- If Creatinine (Cr) increases by >30% evaluate the patient’s volume status and consider reducing/holding diuretic (if volume deplete) before reducing/holding digoxin, ACE-I, ARB, spironolactone or BB

- Referral to a Nephrologist is encouraged when there is kidney impairment as defined by a Cr increase by >30%, an eGFR <30 mL/min or eGFR <45 mL/min if cause is unknown

- If a drug with proven mortality benefit is not tolerated by the patient (because of hypotension, bradycardia or progressive renal dysfunction) then reduce or discontinue other drugs without proven mortality benefit (namely digoxin, diuretics, calcium channel blockers, amiodarone)

- Diuretics are used to control fluid overload but the goal is to use the minimum effective dose. These drugs can sometimes be discontinued once the patient is asymptomatic

- An effective diuretic dose reduction is more often achieved after ACE-I and BB reach target doses

- By using the minimum effective diuretic dose, it is more likely that symptomatic hypotension and/or unacceptable increases in Cr with ACE-I or BB can be avoided

Aggressive Management of Cardiovascular (CV) Risk Factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, obesity) and other comorbid conditions is recommended:

- ASA 81 mg daily for patients with CV risk factors or established atherosclerosis

- Treat comorbidities and risk factors as per current guidelines

11. Indications for Referral to a Medical Specialist

- Cause of heart failure unknown

- Suspicion of ischemia or valvular disease as the primary cause

- Severe heart failure that is refractory or difficult to control

- Symptomatic arrhythmias

- LVEF≤ 35% (consideration of cardioverter-defibrillator implantation)

- Consideration for heart transplantation/implantable defibrillator/cardiac resynchronization

- Serum sodium <132 mmol/L (persistent after water restriction)

- Refer to a Nephrologist when renal function is impaired and/or deteriorating and the reason is not apparent (see chronic kidney disease guidelines)

- Refer to the Heart Function Clinic, Cardiac Rehabilitation or Risk Reduction Centre, and to a local Chronic Disease Management Program where available

- Refer to a Geriatric Medicine Specialist or to Long-Term Care Managers when an elderly patient has significant medical comorbidity, medication management issues, and/or significant cognitive, psychological and functional issues

- Advanced Practice Nurses provide integral specialist support of cardiac care in HF clinics where they provide nursing case management for ongoing surveillance and education of patients and family members

12. Heart Failure in the Elderly

- Elderly patients constitute one of the largest groups of patients with HF

- In general, HF medications are under prescribed despite the fact that this group derives a greater absolute benefit from these medications

- Treatment strategies in the elderly patient with HF are the same as other groups. However, care must be taken with respect to medication initiation and uptitration

- A gentle strategy to maximize long-term adherence is preferred because of the propensity for adverse events in this group (especially postural hypotension and digoxin toxicity)

- Assess for relevant comorbid conditions, such as cognitive impairment, that may affect treatment, adherence, follow-up and prognosis

- Identify a capable caregiver

- Consider referral to a specialist in geriatric medicine and/or community support staff

13. Management of Heart Failure with Comorbid Conditions

13.1. Chronic Kidney Disease

- HF patients with stable renal function (Cr < 200 µmol/L and eGFR >30 mL/min) should receive standard therapy with an ACE-I, ARB or spironolactone (use digoxin with extreme caution)

- Monitor serum Potassium (K+) and Cr levels more frequently, especially with combination therapy or in the case of an acute intercurrent illness

- HF patients with persistent volume overload or deteriorating renal function should be assessed for reversible causes - medications (especially NSAIDs), hypovolemia, hypotension, urinary tract obstruction or infection

- Stable oliguric HF patients - daily evaluation of the dose of diuretics, ACE-I, ARB, spironolactone and non-HF drugs that impair renal function is recommended (preferably as an inpatient)

- Stable non-oliguric HF and Cr increase >30% from baseline - consider reducing the dose of diuretics, ACE-I, ARB and spironolactone until renal function stabilizes

- Referral to a Nephrologist is encouraged when there is kidney impairment as defined by a Cr increase of >30%, an eGFR <30 mL/min or eGFR <45 mL/min if cause is unknown

13.2 Anemia (hemoglobin <110 g/L; generally symptomatic if <90 g/L)

- Investigations and treatment should be directed at the underlying cause

- Substrate deficiencies should also be replaced (iron, vitamin B12 or folate)

- There is no evidence to support the use of erythropoietin (or darbepoietin) in HF

- Consider blood transfusion if, after substrate deficiencies have been corrected, anemia and advanced symptoms persist

14. Management during Intercurrent Illness

- During acute intercurrent illness (i.e. pneumonia, COPD exacerbation) BB, ACEI and ARBs should be continued at their usual dose unless they are not tolerated

- If there is a concern about their use, then the dose can be halved during the illness and then uptitrated rapidly as soon as safely possible

- Only with a life-threatening complication should BB, ACEI and ARBs be discontinued abruptly

- HF patients with acute dehydrating illness should have prompt evaluation of their renal function and electrolytes even if they are not overtly volume depleted or overloaded

- If renal function worsens, adjust doses of diuretics, spironolactone, digoxin, ACEI, ARB as necessary

- If surgery is required, then patients with HF should be evaluated by a Physician experienced in HF management perioperatively

- If a patient with HF develops a gout exacerbation, the preferred treatment would include oral colchicine ± prednisone; avoid NSAIDs due to their role in exacerbating HF. Gout can be prevented with the use of allopurinol and/or a reduction in diuretic dose (as tolerated)

15. Ongoing Management

Comprehensive HF management is based on setting treatment goals and monitoring the effectiveness of management:

- Define and monitor cardiovascular goals and the key clinical indicators using a systematic approach (e.g. electronic medical record, flow sheet, file cards)

- Reverse congestion

- Control arrhythmia and ischemia

- Prevent emboli

- Stabilize vital signs (pulse, sit/stand blood pressure, weight)

- Use current drug and non-drug therapy for HF and for cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidity

- Review medications for intended and unintended effects (inappropriate polypharmacy, potential drug interactions, inadvertent aggravation of comorbid conditions)

- Monitor serum biochemistry (electrolytes, Cr/eGFR) over the short-term (days to two weeks) if the clinical condition or medications have changed . The frequency will depend on whether the current values are normal or abnormal and whether the patient continues to worsen or improve. When stable, remeasurement at six month intervals may be sufficient but will depend on clincal stability and changes in medications

- Monitor serum digoxin only if toxicity is suspected or for checking adherence

- Monitor and treat psychosocial consequences (i.e. non-compliance, anxiety, depression, fear, delirium, dementia, social isolation, home supports and need for respite care)

- Define and re-define the goals of treatment over time with the patient

16. Prognosis of Heart Failure

Outcomes in heart failure are highly variable and it is important to provide accurate information to patients about prognosis to enable them to make informed decisions about medications, devices, transplantation and end of life.

Poor prognostic factors include:

- Recurrent hospitalization for acute HF

- Advanced age (>75 years)

- Female gender

- Ventricular arrhythmias (non-sustained ventricular tachycardia) and atrial fibrillation

- NYHA HF Classes 3 and 4

- LVEF (<35%) or combined systolic and diastolic left ventricular dysfunction

- Marked left ventricular dilatation (LVEDD > 70 mm)

- High BNP levels (See Table 1) - use of BNP for prognostication requires further study

- Low-serum sodium (< 132 mmol/L)

- Hypocholesterolemia

17. Palliative and End-of-Life Care

Predicting time of death in HF is challenging given the cyclical nature of the disease. Helpful clinical prediction tools have been established. Discussions regarding end-of-life care should be initiated with patients who have persistent NYHA Class IV symptomatology or an EF < 25% despite maximal medical therapy (at target doses of study drugs as mentioned above).

Prior to initiating end-of-life care ensure that:- All precipitating factors have been addressed including:

- Residual angina and hypertension

- Adherence to salt and fluid restrictions

- Adherence to medications

- Contributory conditions (arrhythmias, anemia, infections, thyroid dysfunction)

- All active therapeutic options have been appropriately considered:

- The patient is taking maximal medical therapy (target doses of study drugs)

- Biventricular pacing (possibly indicated with QRS > 120 ms)

- Implantable defibrillator (possibly indicated with LVEF < 30%)

- Revascularization (percutaneous intervention or bypass surgery)

- Transplantation options have been explored

- Support of dying patients and their families

- Caregivers should be consulted to determine their degree of burden

- It is important to ensure that advance care planning has been carried out, including financial and health care decisions (e.g. Representation Agreement)

- Control of pain and other symptoms

- Symptoms related to volume overload:

- Adequate diuretic use (sometimes more than one agent) is important

- ACE-I dose may need to be reduced if limited by symptomatic hypotension and renal impairment (Cr > 250 µmol/L or > 30% from baseline)

- Consider choice and dose of narcotic as renal function is likely impaired – i.e. Hydromorphone for narcotic naïve, Duragesic patch. → Consider home oxygen (See COPD Guidelines for indications)

- Decisions on the use of life-sustaining therapies

*Images provided by Microsoft Clip Art

Appendices

Appendix A - DiureticsAppendix B - Beta-Blockers (BB)

Appendix C - ACE-Inhibitors (ACE-I)

Appendix D - Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs)

Appendix E - Direct-Acting Vasodilators

Appendix F - Spironolactone

Appendix G - Digoxin

Figures

Appendix A - Diuretics

Rationale

- Used to control symptomatic volume overload

Beneficial Subsets

- NYHA class II-IV with fluid overload (edema, ascites, weight gain)

Goal/Dose

- Start with furosemide 20 mg/day and increase/decrease as needed

- Divide the doses BID if > 80 mg/day are required

- Aim for minimum effective dose to control symptoms of fluid overload

- If volume overload persists despite optimal medical therapy and progressive increases in furosemide dose (i.e. >120 mg BID) consider:

- Changing furosemide to bumetanide as oral absorption may be improved

- Cautious addition of metolazone 2.5-5 mg 30 min prior to furosemide dose

- Start with a test dose 3 times/week, closely monitoring daily weight, as well as serum K+ and Cr/eGFR

- Note: Diuretics can be stopped once fluid overload resolves

Monitoring

- Check serum Cr, Sodium (Na+) and K+ before initiating therapy and one to two weeks after each dose adjustment

- Watch K+ carefully: maintain K+ between 4.0-5.5 mmol/L

- K+ may increase when using K+ sparing diuretics (spironolactone, triamterene, amiloride), especially when combined with an ACE-I or ARB

- K+ may increase when K+ depleting diuretics decreased/discontinued while patient on K+ sparing diuretic, ACE-I and / or ARB

- K+ may decrease when using K+ depleting diuretics (furosemide, metolazone, hydrochlorothiazide)

Dealing with Side-Effects

- If Cr increases > 30% from baseline, reduce/hold diuretic until volume status normalizes

- If muscle cramping occurs, check magnesium and calcium and replace as necessary

- If nocturia is a concern, avoid diuretic therapy after 2 pm

Appendix B - Beta-Blockers (BB)

Rationale- BB are the most recent dramatic advance in HF medical treatment

- They slow disease progression, decrease hospitalization, decrease mortality and improve quality of life but have little effect on exercise duration

- All patients with chronic, stable HF (volume controlled NYHA Class I-IV)

- Start when there is no physical evidence of fluid retention (i.e. euvolemic), with a heart rate > 60 bpm and a systolic BP > 85 mmHg

- Not to be initiated in volume overloaded, acute or highly symptomatic HF

- Contraindicated in patients with reactive airway disease (asthma) but can be used for patients with COPD, peripheral vascular disease or diabetes

- Monitor blood pressure, pulse rate and HF symptoms with dose adjustments

- Patients may clinically deteriorate over the first 6-12 weeks but persistence is necessary

- Adjustments may be required in the doses of other medication, including diuretics, vasodilators and ACE-I, at least in the titration phase, to increase the tolerance for BB

- Hypotensive effects:

- Consider general measures as above

- Reconsider need for nitrates, Calcium Channel Blockers (CCB), vasodilators and diuretics

- Reassure: Symptoms of dizziness often resolve within 2-4 weeks of titration

- Worsening fluid overload:

- Intensify sodium and fluid restriction and/or increase diuretic dose

- May have to temporarily reduce BB dose until volume control achieved then retry titration (halve dose if serious deterioration)

- Significant bradycardia:

- Obtain an ECG to exclude heart block

- Reduce or eliminate other drugs that also slow heart rate (digoxin, diltiazem, verapamil, amiodarone)

- Reduce dose of BB

- Consider pacemaker support if severe bradycardia or high grade AV block

Beta-Blocker Equivalent Doses

- The effect of BB in HF is not a class effect. It is recommended that patients already on a beta blocker be changed to one of the recommended agents as above

- The following is presented as a rough guide based only on recommended “usual” and “starting” doses. Therefore, it is recommended that patients are followed closely during and after conversion

- The following doses are equivalent to carvedilol 12.5mg BID

Appendix C - ACE-Inhibitors (ACE-I)

Rationale- ACE-Is slow disease progression, improve exercise capacity and decrease hospitalization and mortality

- All patients with HF (NYHA I-IV)

- If baseline kidney function impaired (eGFR <30 ml/min) do not start

ACE-I start hydralazine/nitrate combination and consult a Nephrologist

- ACE-I may cause a deterioration in kidney function and hyperkalemia, so careful monitoring is required during titration phase

- In most situations these drugs can be used successfully with dosage adjustments of concomitant medications

- Check Cr and K+ before initiating therapy and 1-2 weeks after each dose adjustment (sooner for the elderly)

- On stable therapy check Cr and K+ every 3-6 months

- In most situations these drugs can be used successfully with dosage adjustments of concomitant medications ( ie. diuretics, ARBs)

- If Cr increases > 30% from baseline:

- First reduce/hold diuretic for 1-2 days; if no response then reduce/stop ACE-I and consider hydrolyzing/nitrate combination

- When there is uncertainty about the underlying cause of kidney impairment or management thereof, referral to a Nephrologist is encouraged

- Intractable cough or drug-associated rash:

- First ensure that cough is not due to poorly controlled HF

- Stop ACE-I, consider ARB or hydrolyzing/nitrate combination if ARB not tolerated

- Angioedema may occur with ACE-I (may recur with ARB therapy)

*Target dose used in large CHF trials with clinical endpoints.

*Target dose used in large CHF trials with clinical endpoints.

Appendix D - Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs)

Benefical Subsets- NYHA Class II-IV

- ARBs are not first-line agents and are reserved for patients intolerant of ACE-I or BB or for patients in NYHA class II and IV HF despite treatment with both ACE-I and BB

- See above - Same as ACE-I

- Note: Angioedema may recur with ARBs

Appendix E - Direct-Acting Vasodilators

Rationale

- Hydralazine and nitrates in combination are effective at reducing afterload and preload with a mortality benefit that is inferior to ACE-I. For this reason ACE-I are generally preferred

- May have greater benefit in patients of African-Canadian descent

- Not associated with renal failure or hyperkalemia

- ACE-I intolerant patients

- Note: Nitrates can also be useful to relieve orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, exercise-induced dyspnea or angina (tablet, spray or transdermal patch)

- Hydralazine results in a tachyphylaxis and may worsen myocardial oxygen demand

- Nitrates require a “drug free” interval, usually 12 hours, to decrease resistance

- Hydralazine and nitrates should be used concurrently

Appendix F - Spironolactone

Rationale- Although a K+ sparing diuretic, this drug exerts its beneficial effects in HF through aldosterone antagonism

- Spironolactone decreases mortality and hospitalization and improves symptoms

- NYHA Class III-IV moderate to severe systolic heart failure

- Extreme caution should be used when adding spironolactone to ACE-I and ARBs due to a propensity for hyperkalemia

- Avoid use in patients with renal dysfunction

- Hyperkalemia may develop if K+ depleting diuretic dose is decreased

- Start at 12.5 mg daily and titrate to 25 mg daily as tolerated (>25 mg rarely indicated)

- Check K+, Cr and eGFR at 3-7 days and 1-2 weeks after each dose adjustment

- Gynecomastia is known to occur in up to 5-10% of males

Appendix G - Digoxin

Rationale- Digitalis may improve symptoms, exercise tolerance and quality of life, but it has not been shown to improve survival

- NYHA Class II-III Systolic HF (digoxin has no role in HF with PSF with normal sinus rhythm)

- Digoxin should be used with caution, especially in women and those with impaired renal function

- Usual dose is 0.125-0.25 mg/day through level 0.65-1 nmol/L 8-12 hours post-dose

- As digoxin levels are typically drawn in the morning, digoxin should be dosed in the evening

- Digoxin: Dose will need to be adjusted in the elderly, those with low body mass, those with impaired renal function and those taking amiodarone

- Electrolytes, Cr and digoxin serum concentrations should be obtained 5-7 days after dose adjustments (approximate time to steady-state)

- Note: It may take 15-20 days to reach steady-state in patients with renal dysfunction

- Obtain a digoxin level whenever toxicity is suspected

- The most important toxic effects are life-threatening arrhythmias (e.g. ventricular tachycardia/ fibrillation, complete atrioventricular block)

- Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, diarrhea, confusion, amblyopia, and, rarely, xerophthalmia may occur

- Note: If hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia (often due to diuretic use) is present, even lower doses and lower serum levels can cause toxicity

Figures

Patient Management

Care Protocols

Care protocols, like medical and nursing procedures, allow staff to offer a consistent approach to managing clinic patients. Care protocols will allow caregivers to establish routines and govern tasks that are performed in the HF clinic as well as tasks that involve other hospital departments and outside agencies. Protocols ensure that key steps are taken to fill potential gaps in the system of care as the patient moves from clinic to hospital or from hospital to clinic.

The development of the following protocols may assist in enhancing the overall management of clinic patients:

- A protocol for patient referrals, which would involve two sub-protocols: one for patients who are referred for medical assessment, another for patients who are referred for patient education

- A protocol for discharge from hospital: this protocol would stipulate that a patient is either seen at discharge or at the clinic within 5 working days, or a telephone follow-up 2 days post-discharge will occur. This protocol should also describe clearly the sequence of events that occurs after discharge to ensure patients understand their care path

- A clinic notification protocol to outline when a patient has contacted the clinic about problems, and how those problems were dealt with. Guidelines for dealing with urgent vs. non-urgent calls

- A protocol for discharge from the clinic

Data Collection

Recent data suggest that, despite medical intervention, HF mortality remains high at a time when morbidity and mortality rates from other common cardiovascular diseases (such as myocardial infarction) are on the decline. Many heart failure patients experience frequent acute medical crises resulting in high hospital readmission rates and increased health care costs.

There is an urgent need to reduce mortality and morbidity associated with HF, reduce hospital admissions and readmissions, and improve patient management. HF clinics have been shown to be an effective alternative to inpatient management of this patient population.

Data collection, using a standard data-gathering tool, will allow practitioners to review and change practice patterns to enhance patient care and improve the quality of life for HF patients and their families.

In general, data collection will allow practitioners to monitor patient issues, measure clinical outcomes, track public health data, document the need for a HF clinic, secure clinic funding, and answer research questions.

Care Plan

A patient care plan, which specifies interventions and teaching done by staff and the anticipated patient outcomes, should be initiated and followed on all patients.

Such a care plan will ensure that patients receive optimum care and understand all facets of their diagnosis and long-term care. Care plans should be customized to meet the individual needs of each patient and should be developed with input from patients and family members.

Moreover, a care plan enhances communication and ensures continuity of care.

*Draft changes pending adoption by CHFNStarting a HF Clinic

Assembling the Team

At a minimum, team members starting a multidisciplinary HF clinic should consist of:

Executive SponsorThis person should be a member of the hospital executive who give the clinic the “rubber stamp” of approval and who will advocate on the clinic’s behalf.

Administrative Leader

The administrative lead should have the ability to hire staff, ensure the day-to-day operations are in order, provide support where needed and arrange for appropriate space and resources.

Physician Leader with expertise in HF Care

The Physician should provide clinical leadership as well as active involvement in preparing the protocols and pathways required for good patient care. The Physician should be committed to providing this leadership.

Nurse(s) with skills in heart failure and patient teaching

Within the multidisciplinary model, the Nurse should have extensive cardiac experience, specifically in HFcare. The Nurse should have skills in education and understand the concepts of chronic disease management.The level of nursing support decided upon may vary from clinic to clinic. Some clinics prefer the Nurse Practitioner role, others an expert Registered Nurse and others a hybrid of both roles. This is a decision that needs to be made with the team from the outset. Nurse Practitioners can provide a wider scope of care, whereas the registered nurse can practice with Physician orders. The scope of practice varies between provinces and we recommend that this is ascertained before starting.

- Able to provide heart failure self-management teaching and support

- Advanced cardiac assessment skills

- Confidence to introduce the concept of end of life planning

- Safely provide telephone support/advice to patients

- Able to use word processing, email, and spreadsheets on computer

The Clerk should be responsible for making appointments, registering the patients, phoning patients before the clinic, filing, preparing charts for the visit, taking calls, collating lab and test results for checking by the Physician/Nurse Practitioner.

Programs with the following resources should also consider support from the following health care providers:

- Pharmacist

- Dietitian

- Physiotherapist

- Social Worker

- Palliative Care

- Geriatrician

- Palliative Care

- Occupational Therapist

Staffing Levels

It is not easy to determine staffing levels. First, it is important to determine how many patients the clinic may expect. To do this, data around local HF demographics should be sought and a clear care pathway be defined to ensure that once the endpoint is reached that the patient is discharged back to their referring source.

A survey to determine patterns of staffing in heart function clinics across Canada was performed in 2004 (presented at Canadian Cardiovascular Congress, 2004 by Kaan A, Clark C and Edmonds M). Fifteen clinics responded and showed that:

- Most clinics (87%) function using the “Nurse-managed, Physician-directed” model of care. Meaning that the day to day function of the clinic is managed by the Nurse, however the care of patients is directed by the Physician. One clinic was directed by a Nurse Practitioner. As this survey is now 6 years old, this model may have changed somewhat

- 40% of clinics see 10-19 patients per week. There was great variation in the number of patients seen as some clinics were just one session per week and some ran 5 days per week

- On average, clinics see 8 patients per session

- Average caseload of RNs was 136 patients (range 60-200). One Nurse saw 10 to 20 patients per week

- One Clerk manages an average caseload of 50 patients per week

- 25% of nursing time involved clerical duties and data entry, the rest was telephone support, clinic visits and patient education

There must be a commitment to meet regularly to assess staffing levels based on the patient load and whether or not the patients are appropriate for the clinic.

Developing a Clinic Philosophy

The philosophy of the HF clinic should be spelled out early on. What is it that the clinic wants to achieve? This focuses the team and allows for planning of services.

Identifying Key Indicators

It is important to identify what indicators the clinic will measure to determine success and monitor progress. The CHFN recommends the following indicators: symptoms, quality of life, heart function, HF hospitalizations, CV hospitalizations, and survival.

Measuring Outcomes

Membership to the CHFN facilitates access to the National Database. For more information on applying for membership please go to https://www.chfn.ca/how-to-become-a-chfn-site. Each new centre needs to have:- A Physician leader of the HF clinic

- A commitment to HF management and follow up

- A Nurse (full or part time) with special expertise and training in HF management

- A sufficient number of HF patients and referral community

- A commitment to enter their patient data into the database with regular downloads to national database

- A willingness to sign a contract of agreement.

The database is designed as a local tool like an electronic medical record but also allows download of data without specific patient identifiers to the National Database. The data that is uploaded is secure and password protected, as the upload technology uses the same encryption technology used for online banking. All patients must sign a consent form before their unidentified data can be entered into the database and uploaded to the national database. There is a consent template located in the members section. Once we have approved and received your signed Program Agreement, you will get a username and password for the website.

Support

What we can give to you is the database to help organize and track your patients locally (you ‘own’ this data), opportunity to benchmark your clinic with the National data, opportunity to ask research questions of your data and that of the National data, use of the data to lobby more effectively for local resources, an invitation to come to our annual meeting currently held in conjunction with the Heart Failure Society of America in September, networking with like minded colleagues to improve the management of HF patients and to learn together, and access to all benefits of the website and the Network.

Team Development

The clinic should meet each month at least to review difficult cases, prepare a plan and to review clinic issues. An agenda should be prepared and action items prepared. Once a year, it is valuable for the team to meet in a “retreat” style to review outcomes, revise the goals and plan for the year. The CHFN database is able to provide centre specific reports that allows a program to track outcomes.

Documentation

Some sample documentation is included that may help with preparing local documentation:

Patient Education

Introduction

Patient education is one of the most important functions of a heart failure clinic, and is the key to the success of a HF management program. Education should involve all members of the multidisciplinary clinic team and must be ongoing.

Health Professional Patient Education

Introduction

Patient

education is one of the most important functions of our heart failure

clinics. This education comes from all members of the

multidisciplinary clinic team responsible for your care and is

ongoing.

Patient

education is one of the most important functions of our heart failure

clinics. This education comes from all members of the

multidisciplinary clinic team responsible for your care and is

ongoing.

This section presents a brief overview of state-of-the-art clinical information for health professionals who care for health failure patients. There are six (6) educational sections. You may use this section as a review for yourself prior to patient teaching. In additional, the eight (8) patient information sections allow you to teach directly from the pages.

Members of CHFN may wish to use the information provided as a reference tool and use a flip chart or other medium to share the information with patients and their families. The patient information sheets are also supplied as information pads that are numbered for each section/topic. Members may distribute the sheets following each educational intervention:

Pathophysiology of Heart Failure

'Chronic Heart Failure' or 'Congestive Heart Failure'?

The word “congestive” means different things to different people and leads to a great deal of confusion. Overall, it is better to discuss “heart failure” with your patients. Different kinds of heart failure include:

- Acute heart failure

- Chronic heart failure

- Systolic heart failure

- Diastolic heart failure

- Left ventricular heart failure

How the Normal Heart Functions

The heart is a hollow muscle about the size of a fist. A normally functioning heart is one of the strongest muscles in the human body. It pumps blood through the lungs to deliver oxygen to the remainder of the body.

The heart is divided into four cavities: two atria and two ventricles. The left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the lungs. From there, the blood passes to the left ventricle, which pumps it via the aorta through the arteries to supply the tissues of the body. The right atrium receives the blood after it has passed through the tissues and given up much of its oxygen. The blood then passes to the right ventricle, and then to the lungs, to be oxygenated. The heart tissue itself is nourished by the blood in the coronary arteries.

Definition of Heart Failure

Heart failure (HF) is a state in which the heart is unable to pump blood at a rate that meets the requirements of metabolizing tissues or can do so only from an elevated filling pressure.1

The incidence of heart failure rises with increasing age, and is three times more likely to occur in men than women. Analysis of numerous published studies indicates that the incidence of heart failure is between 2.3 to 3.7 per thousand per year.2

Usually, HF manifests initially during exertion, however, as the disease progresses the contractile performance of the heart deteriorates and shortness of breath and fatigue result, even when the body is at rest.

Etiology of Heart Failure

The two main causes of HF are:

- Myocardial infarction, with loss of heart muscle secondary to coronary artery disease

- Chronic hypertension

Heart failure can also result from:

- Viral infection of the heart

- Valvular disease

- Alcoholism or other toxins

- Congenital conditions

- Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Heart failure can be aggravated by:

- Diabetes

- Anemia

- Thyroid disease3

| Left heart failure (low output/pulmonary congestion) |

Right heart failure (systemic venous congestion) |

| • Dyspnea • Orthopnea • Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea • Fatigue • Cough |

• Peripheral edema • Weight gain • Anorexia • Abdominal discomfort • Fatigue |

These symptoms may be accompanied by:

- Angina

- Cool extremities

- Tachypnea

- Tachycardia

- Elevated jugular venous pressure

- Positive hepato-jugular reflux

- Rales, wheezes

- Added heart sounds

- Pleural effusion

- Detection of enlarged heart on x-ray4

References

- Colucci W, Braunwald E. Pathophysiology of heart failure. In: Braunwald E, ed. Heart disease. 5th Edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997;394-420.

- Cardiology Preeminence Roundtable. CHF in Brief. In: Beyond four walls: research summary for clinical and administrators for CHF management. Washington D.C.: The Advisory Board Company, 1994.

- Adams KF, Zannad F. Clinical definition and epidemiology of advanced heart failure. Am Heart J 1998;135(Suppl 2, Part 6):S204-S215.

- Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Report on the 1993 Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Heart Failure. Guidelines for the management of heart failure. Toronto: Publications Ontario, 1996.

Dietary Considerations

The relationship between proper nutrition and control of heart failure is well understood: low salt intake, reduced alcohol consumption, and a well-balanced diet are the mainstays of helping patients manage HF.1

When discussing diet and nutrition, it is important to involve the patient’s spouse, family members, and caregivers. In many cases (particularly with men) HF patients are not the primary food preparer in the household and may be unaware of the caloric, salt, and fat content of the foods they’re ingesting. In cases where a patient’s diet must change, involving their family in these changes will promote compliance.

Canada’s Guide to Healthy Eating offers an excellent template for counselling patients about diet. Encouraging patients to eat foods from the four major food groups will ensure they get their daily requirement of essential nutrients and vitamins.

All heart failure patients should receive written dietary guidelines, reinforced orally by the clinic nurse during regular clinic visits. Those with limited reading ability and certain ethnic groups with unique food preferences should receive specialized counselling.1

Lowering Sodium Intake

Sodium intake should be limited in patients with HF because it is

not efficiently excreted

from their system. In patients taking diuretics, the drug is rendered

less effective

when sodium intake is not limited.2

The average person requires less than 500 mg/day of sodium, however, most consume between 5-6 grams/day. The optimum daily salt intake for HF patients is 2 grams/day or less, however, some patients find their diet unpalatable at this level. Therefore, depending on their stability, this level of sodium intake may be increased to 3 grams/day.1 Patients taking large amounts of diuretics (>80 mg/day of furosemide) need to maintain their sodium intake at 2 grams/day or less. However, for patients with mild to moderate, stable heart failure without fluid retention, 3 grams/day is a reasonable target.1

In order to increase compliance with a low-sodium diet, patients should be advised to:

- Stop using the salt shaker (remove it from the dinner table)

- Not add salt to food during preparation

- Read food labels carefully

- Stop eating processed and high-sodium foods: the greatest source of sodium (up to 80%) is the salt and other sodium compounds added to food during processing

- Be aware of ‘hidden’ sources of sodium: for example, one slice of bread contains only 150 mg of sodium, however, the quantity of bread eaten during one day could cause total daily sodium intake to be high

Assessing your Patient’s Sodium Intake/Setting Goals for Reduction

Questions that will help assess your patients’ sodium intake are:

- Who prepares your food?

- Is salt added during food preparation?

- Do you add salt to your food at the dinner table?

- How much bread do you eat?

- How often do you eat in restaurants?

- Do you request that your food be prepared without salt or monosodium glutamate?

- How often do you eat processed food (frozen dinners, canned soups, salad dressings, luncheon meats, cheese)?

To ensure compliance with a reduced-salt diet, set small, incremental, achievable goals with your patients (i.e. cut out salt during food preparation, take the salt shaker off the dinner table, stop eating fast food or prepared food). To give patients ‘control’ over their health care, allow them to prioritize the changes they need to make, but help them determine which actions will have the greatest impact on lessening sodium in their diet.

Use this chart to discuss common foods and their sodium content:

|

Alcohol

Acute ingestion of alcohol depresses myocardial contractility in patients with known cardiac disease. If alcoholism is the suspected cause of a patient’s HF, alcohol intake should be strongly discouraged. For patients with Class I or II HF, ingestion of alcohol should not exceed one drink per day, i.e. 30 mL of liquor, or its equivalent in beer or wine.1

Smoking

Abstinence is recommended for all patients, especially those with ischemic heart disease (IHD).2

Fluid Restrictions

Unstable HF patients should ingest no more than 1 litre of fluid per day. The recommended daily intake for stable HF patients is 2 litres, which is equivalent to about 6 glasses of water. However, patients must be counselled that not all fluid intake comes from drinking liquids, and that fluid contained in foods such as fruit or soups must be factored into their daily calculation.2

Daily Weigh-in/Weight log

Patients’ weight should be taken and recorded during every clinic visit, to determine whether it has remained stable or if they are experiencing undue water retention. Patients should also be encouraged to weigh themselves daily – particularly if they are taking diuretics – to monitor their weight. Specific instructions to patients include: weigh yourself after emptying your bladder, before breakfast, every morning, wearing the same type of clothing, and using the same weigh scale.

Patients must be counselled to seek medical help immediately should they gain or lose weight quickly. A daily weight log will help monitor weight and encourage control over drug (diuretic) therapy.

Vitamin Supplementation

Vitamin supplementation may be considered for severe HF patients, since vitamin loss may occur with marked diuresis.1

References

- Dracup K, Baker D, Dunbar SB, et al. Management of heart failure: counselling, education and lifestyle modification. JAMA 1994;272:1443-1446.

- Uretsky BF, Pina I, Quigg RJ, et al. Beyond drug therapy: nonpharmacologic care of the patient with advanced heart failure. Am Heart J 1998;135(Suppl 2, Part 6):S264-S284.

Exercise

Until recently, exercise was contraindicated in patients with HF. However, lack of activity may have long-term detrimental effects on physical functioning. Numerous studies have shown that patients with HF can safely engage in suitable physical activity and improve their exercise capacity.1 In fact, one recent study suggests that higher levels of activity are associated with increased levels of functioning and wellbeing for patients with chronic HF.2

While stressing the seriousness of your patient’s illness and disease progression, you can also encourage an exercise plan that enables them to remain active and enjoy a reasonable quality of life.

Unfortunately, many patients diagnosed with HF were overweight and inactive prior to development of the disease. As a result, it can be a challenge to initiate an appropriate exercise program to which patients will adhere.

The functional classifications of heart failure can serve as a guide to determine the safest level of activity for your patients:

| Class I: | No limitation of physical activity. Exercise for 30 minutes or longer. |

| Class II: | Slight limitation of physical activity. Most physical activity needn’t be restricted, however, ordinary exercise may result in fatigue or dyspnea. |

| Class III: | Marked limitation of physical activity. Ordinary forms of exercise should be moderately restricted. The patient may only be able to walk 10 minutes per day. |

| Class IV: | Severe limitation of physical activity. Any strenuous activity can increase discomfort and result in shortness of breath or angina. |

Helping your Patients Establish Realistic Exercise Goals

- Assess your patient’s current level of physical activity by

asking the following questions:

- How many blocks can you walk before getting short of breath or fatigued?

- Are you breathless with minimal exertion, or when you wake up?

- Do you have chest discomfort when walking?

- What type of activity do you enjoy now? In the past?

- Involve your patients in the management of their diagnosis and empower them to take responsibility for their well-being.

- Assist your patients in developing a regular, progressive exercise program that will help them to increase their endurance gradually, at their own pace.

Tips for Discussing Exercise with your Patients

Explain the benefits of exercise:

- Improved muscle strength and tone

- Reduced effects of osteoporosis

- Improved functional capacity

- Improved quality of life